November is the time we finish our last major chore of the season; winterizing.

Winterizing actually begins much earlier in the season during the summer. It’s a process of keeping the colony healthy and large so they are able to fight off pests and disease. We do our best to treat for pests as needed. The Varroa mite is a terrible scourge on the hive and we work to minimize their numbers throughout the year.

After August’s honey harvest, we treat and then assess the forage potential going into the fall. We want the bees to collect as much nectar and pollen as possible since it’s the healthiest food they will heat. If there are any shortfalls in foraging, we will begin to feed the bees sugar syrup by mid-late September to fill up the last remaining spaces in the hive. Sugar syrup does not contain the same nutrition nectar does, however it can bridge the gap for a colony through the winter. We want colonies who can withstand the cold winter months and the pests and diseases they encounter. In my view, starving to death is not an acceptable way to cull out weak hives. Even strong hives can die without proper food storage.

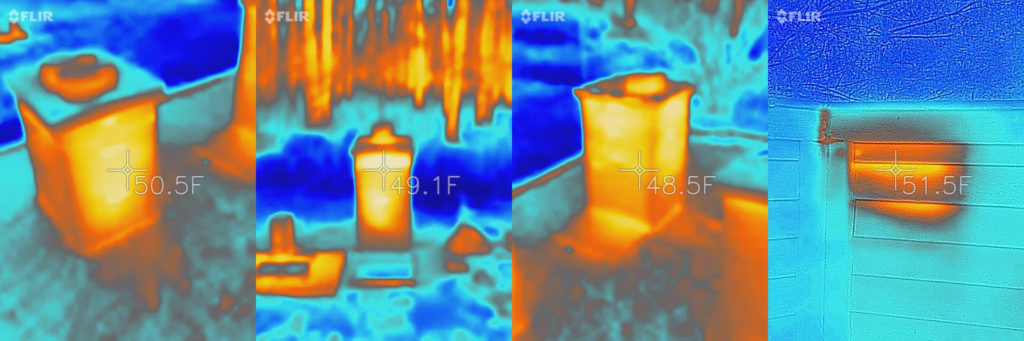

November finally comes along and it’s time to do our last hive checks for the year. Generally I check the exterior of the hives and try not to open the boxes. If I must crack open the boxes, there’s not usually a need to pull any frames. I am able to assess the food stores by looking between the frames at the top and bottom of the boxes, as well as determine the population size of the cluster. At this point of the year and if I’ve done my work right for the year, I want that cluster to be reaching across the boxes. Another way to determine this is to use a FLIR camera to look at the size of the hive’s heat signature. Many beekeepers do this, however I haven’t used one before myself.

Finally, it’s time to wrap the hives. I use black roofing paper and staple it around the exterior of the hives. The idea behind this is to absorb UV energy on sunny winter days as well as to cut down on drafts through the cracks between the boxes. I will then put a vent box on the top of the hive to allow for moisture to escape and a space for sugar. Inside the vent box I put a piece of newspaper across the tops of the frames and pour on a few pounds of dry sugar. The sugar will absorb extra moisture and become an emergency food source if the bees need it. The inner cover and a piece of insulation go on top of the vent box and finally the outer cover goes on. I’ll throw a ratchet strap around the hive to keep it anchored down, and we’re done.

Over the winter, I will go out on warmer days to look for activity. In January I do a mite treatment to try to knock down any mites I can. Sadly, we may lose some hives, but if we’ve done everything we can throughout the previous year, we should keep our survival rates pretty high.

Disclaimer: As with many tasks in beekeeping, there are many ways to accomplish them successfully. This is merely what I’ve found that works for me and my hives. It’s not necessarily better than other techniques.